Eighteen months.

That’s how long my wife and I put our lives on hold to live with parents and save for our future. No place of our own. No wedding date circled on the calendar. No kittens running around the floor, even though we badly wanted them. Just a bet that patience and discipline would lead us to the life we wanted.

We told ourselves it was temporary. That the sacrifice would make the reward sweeter. We’d scroll through Zillow together and think, “just a little longer.” We were doing the right thing. The responsible thing. The kind of thing adults are supposed to do when they’re building a life together.

We didn’t do it perfectly. Our savings sat in a checking account when they could’ve earned more in stocks or a money market fund. But still — eighteen months. Long enough to feel like we’d honored some unspoken social contract: delay gratification now, earn stability later.

Except when the moment came, the finish line had moved. The homes we thought we were saving for were suddenly out of reach. The life we thought we were buying had been repriced.

And it wasn’t just houses. Everywhere I looked, the essentials — food, childcare, energy — had been repriced upward. And the same was true, even more dramatically, across financial markets. Wages rose a little, sure. But it felt like the world had shifted from rewarding income to rewarding the very assets we didn’t own.

A year and a half of paychecks felt like bringing a knife to a gunfight. Our savings didn’t stack up against anything scarce because those things had been repriced in a new currency. Ownership itself. That realization pushed me to dig deeper, to understand how the landscape had shifted.

So what happened? It’s what I’m calling the Great Repricing — a shift so seismic yet so subtle that I think many still don’t see it. But once you do, you can’t unsee it. The game has changed. And the challenge now is learning how to play by the new rules.

The first metric to consider when assessing the post-pandemic economy is a term economists refer to as M2. It tracks the amount of spendable dollars circulating in the system.

Whereas M1 covers the most liquid forms of money, like cash in your pocket or checking accounts, M2 goes a step further. It also includes savings accounts and other balances that aren’t instantly spendable but can be tapped quickly if needed.

The U.S. money supply was once tethered to hard constraints. That began to change in 1971, when President Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold. Freed from that anchor, the system evolved into the credit-driven economy we know today, one in which Congress can authorize massive fiscal spending and the Fed can rapidly expand the monetary base.

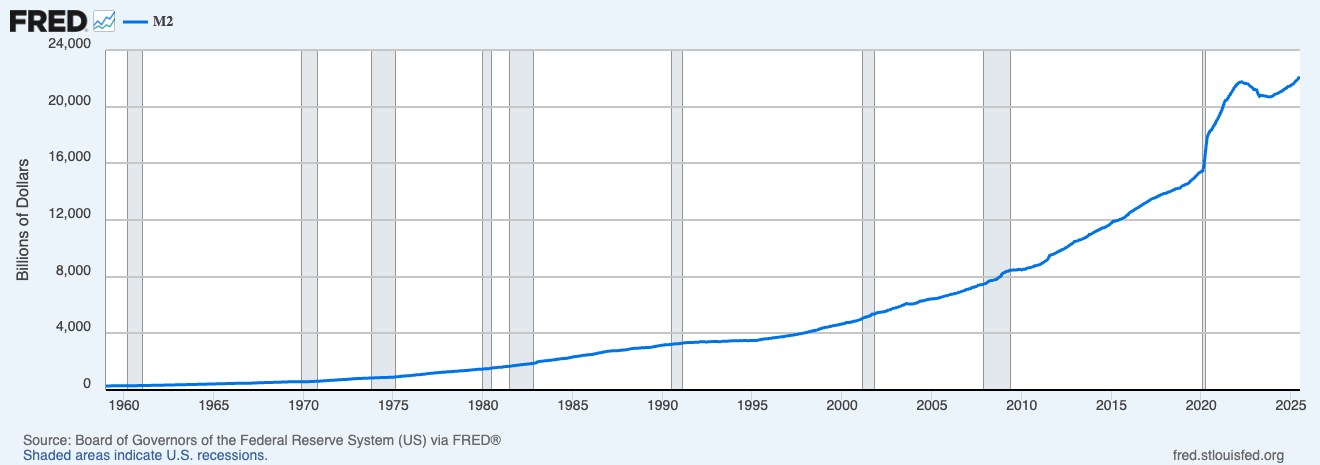

Since then, here's what has happened to M2:

Some historical events to consider:

1971 — U.S. leaves the gold standard

1980s–2000s — Tight policy and globalization fuel decades of low inflation

2008 — Financial crisis triggers QE and near-zero rates

2020 — COVID stimulus leads to unprecedented money creation

2022 — Fed tightens as inflation returns while M2 contracts

For decades, the line mostly trended higher, but then it went parabolic in 2020. Instead of prices drifting upwards like they always had, they jumped. This was the break in continuity my wife and I felt while trying to save, where scarce things became permanently repriced upward.

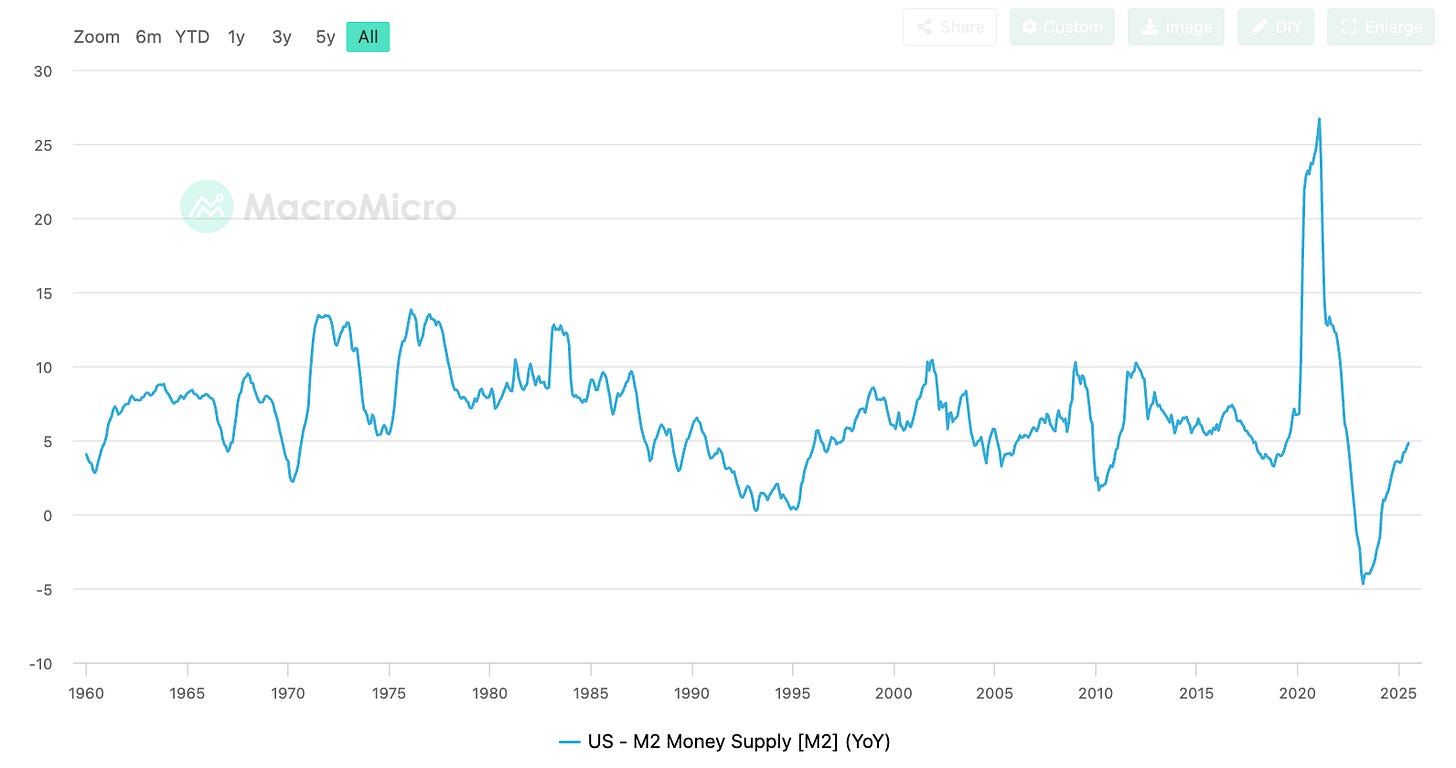

The year-over-year money supply series further shows how historically significant this was:

We’ve never seen a spike like the one we experienced at the onset of the pandemic.

Of course, it’s only fair to acknowledge the sharp decline that followed. After surging in 2020 and 2021, the money supply contracted — a move that, at first glance, might make it seem like everything eventually evened out.

But look closer at the chart. YoY M2 fell 5% at peak, but that was after climbing by over 25% right before. And it’s already back to climbing again.

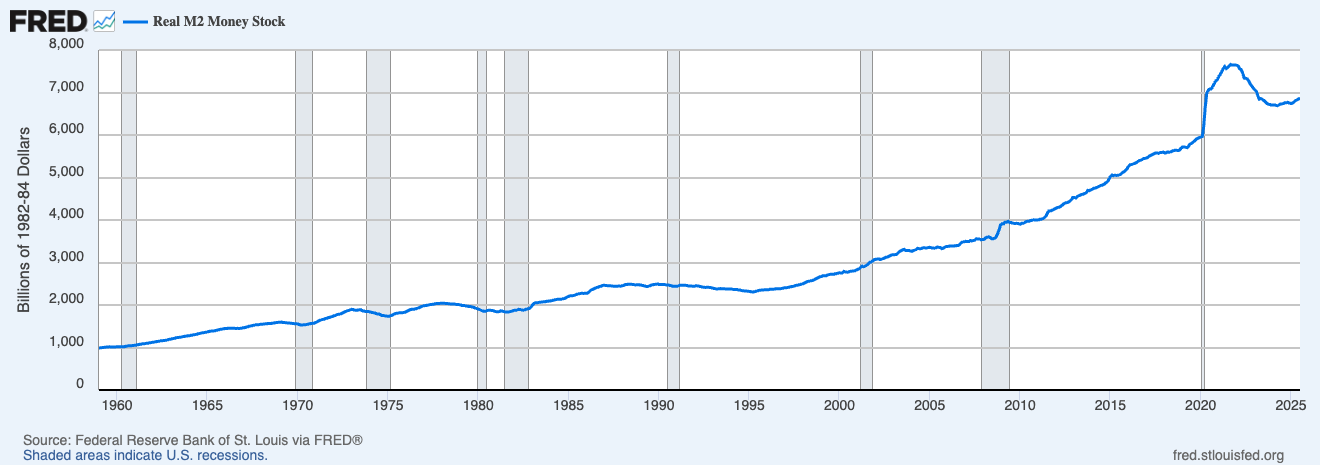

To better understand what actually happened, we need to look at one final chart: M2, adjusted for inflation.

Unlike the smooth upward slope of nominal M2, the inflation-adjusted version is choppier throughout history, which better reflects how real life has felt over time. Purchasing power doesn’t move in a straight line, and real M2 captures that.

During the COVID period, real M2 spiked alongside nominal M2. But today, the former isn’t sitting at an all-time high. It remains well above pre-pandemic levels, which helps explain the higher prices and asset valuations, but it has declined from the peak reached during the stimulus-driven surge. That’s why life still feels more expensive, and why many people feel less wealthy than they did just a few years ago.

This brings us to the deeper concept of dilution as a silent tax.

While inflation is evident to anyone buying eggs at the grocery store, dilution is more hidden. It’s the idea that when the supply of money expands rapidly, the value of each dollar quietly weakens.

Most people don’t study M2. They don’t track how many dollars are circulating in the system. I certainly wasn’t when I sold my Pokémon cards five years ago.

I know — to children of the late ’90s like myself, that feels like a betrayal. And believe me, it did at the time. But a buyer was willing to take them all off my hands for a price that genuinely shocked me.

I knew they were somewhat valuable, mostly originals from the base set. I even had a few unopened packs. And while I understood they were rarer than any new product coming out, I wasn’t fully thinking through a scarcity-first mindset. Definitely not in relation to what that check I received was actually worth.

I’m not trying to paint a picture that I sold for pennies on the dollar, because I didn’t. But I do want to emphasize the idea of dilution. There will only ever be so many 1st Edition Charizards. But there can (and definitely will) always be more dollars.

It’s on a much smaller scale, but the same principle applies to housing, especially in areas where people most want to live. As the money supply spiked to historic levels through 2020 and 2021, those with an investor’s mindset started shifting their newfound cash into anything scarce.

The most prudent uses were to buy stocks, gold, Bitcoin, and real estate — assets that tend to retain their value during periods of inflation.

Other cash went into collectibles. My dad ran a sports card store at the time, and it was one of the best periods the hobby had seen in decades. Collectors wanted to buy, sell, and transact. Prices were rising, just as they were in the housing and equity markets.

Of course, not all of that liquidity went to productive places. There was day trading, NFTs, and meme coins. Speculation was rampant, so not everyone exited this period a winner. But those who did won big. And while the era of stimulus checks landing in everyone’s bank account is over, another form of government spending isn’t slowing down anytime soon.

In Part 2 of the Great Repricing, we’ll cover where M2 structurally goes from here, what it means, and actionable takeaways.

Thank you for reading. If you’re enjoying these market/macro pieces, please subscribe, like, comment, or reach out in some form with your own stories from this period.